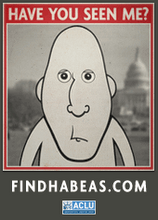

There were plenty of anthems available for Black Lives Matter and Occupy, but few people heard them. And all the corporations, including music companies, who had pledged DEI strategies in 2016, dropped them all in less than a decade. 2011-2019

The explosive, yet transient, expansion of the Occupy movement in

2011-12, and the Black Lives Matter movement in the months prior to Trump’s

victory in 2016, signaled a growing realization by corporate America, including

the music industry, that it had better act “woke,” even if concern for subjects

like economic or racial justice was pretty superficial. While it took the

arrival of Trump to really spur the arch-right-wing musical outliers, the

greater noise made by right-populist musicians like Ted Nugent, Kid Rock, and

Ariel Pink, had the paradoxic effect of showing that the assumptions among most

pop artists that they should provide lip service to social-justice movements had

already spread through most sectors of the music business.

The decentralist and pop-up nature of Occupy

meant that plenty of musicians showed up in various cities at spontaneous

concerts, but the plans to create benefit albums mostly were shelved, because cities cracked down on

encampments quickly, and Occupy had fizzled as a long-term movement by

mid-2012. Black Lives Matter, by contrast, experienced continued surges in

2016, 2018, and throughout the early months of the pandemic, due to specific

acts of police violence. As a result, musicians from Algiers to Deerhoof issued

music dedicated to BLM. It was easy for

musicians to pledge support for BLM, and this helped push corporations into

more enlightened DEI (Diversity Equity Inclusion) strategies. (The near-universal

corporate rejection of pledges for DEI and LGBTQ+ rights during the election

year of 2024, due to the mere threat of a second Trump victory, showed how

transitory and downright fake these corporate pledges had been.)

Indie was going through a

distinct “loud/soft” transition, with new acts like Florence and the Machine

and existing acts like Mogwai stressing emphatic delivery, while Decemberists,

Laura Marling, and the Civil Wars strived for understatement. And a new round

of comical chaos was in gestation through bands such as Parquet Courts, Car

Seat Headrest, and Ought, a movement that would reach fruition in the U.K., and

in stateside bands like Bodega, as the 2020s began.

Some millennials,

particularly those who had not been around for indie-rock mini-surges in the

1990s and 2000s, like to talk about the “indie boom” of the second Obama

administration, though this was dominated by more pop-friendly bands like

Foster the People, fun, Bastille, and Kings of Leon. In fact, one could argue

that sadcore women artists such as Lana Del Rey and Lorde arrived because too

much of the music scene was oppressively sparkly-happy. Rather than dismiss the

happier boom as too pop-centric, it helps to reiterate my earlier observation

that every subgenre reinvented itself every few years or so. If you were a

teenager during the 2010-16 period, the new music sounded just as legit as that

favored by indie fans in the previous two decades. As indie became more

pop-centric, it crossed over into collaborative efforts with R&B and

hip-hop worlds as well, with songwriters like Grimes and Caroline Polachek

co-writing songs with the likes of the Knowles sisters and Janelle Monae. Many

thought that indie had no center of gravity during the 2011-17 period; in

reality, the center of gravity was everywhere.

But it was more than possible

for DEI and woke strategies to misfire; in fact, artists that had launched

earlier in the millenium were realizing that they had to pay attention to

rapidly shifting social cues with faster response times than their predecessors

ever did. The problem rarely reached the level of the type of “cancellation”

experienced by J.K. Rowling during the waning Obama years; instead, artists had

to pay attention to new feminist booms or queer political booms that drove

emerging artists like Sophie, Chappell Roan, Snail Mail, and boygenius. And if

they were slightly behind the curve, the results could be harsh. At the height

of her popularity, Katy Perry released “Firework” in 2010 to a chorus of

skeptics wondering if her feminist lyrics really rang true. By the time her

“feminist anthem” 143 was

released in 2024, the images and references seemed so cliched, the album

quickly tanked.

Despite a burst of recorded

activism by bands like L7 following the January 2017 Women’s March that

heralded Trump’s assumption of power, it should have surprised few observers

that the first two years under Trump would involve a turning inward similar to

the Reagan era. At least in the indie community, that meant the release of

exceptional but deeply personal works from artists such as Mt. Eerie, Julien

Baker, Tyler the Creator, and Circuit des Yeux. In the pop world, Top 40

artists recycled an endless series of duo collaborations among the likes of Ed

Sheeran, Quavo, Selena Gomez, Chainsmokers, Miley Cyrus, The Weeknd, and many

many more, most relying on heavily hedonistic themes. The presence of newcomers

like SZA and Halsey guaranteed some salvageable elements in the forgettable pop

of the late 2010s, and 2017 displayed an occasional riff-heavy tune like

Portugal the Man’s “Feel It Still,” but the early Trump era proved as sobering

as the 1980s descent into dance hell. The sudden popularity of BTS might lead

some to conclude that K-pop provided a bright spot in a forgettable U.S. pop

realm, but to my ears, K-pop only reinforced the conclusion that the era was a

lame one.

During the Trump era, R&B

artists tended to make wiser use of pop charts than did indie or country

artists. Where the latter would continue to drop a lone single on the charts to

gauge consumers’ receptivity, Ariana Grande or Bad Bunny would release an

entire album at once in streaming media, and have ten or more singles on the

charts as a result. The physical album products in LP or CD might be delayed

for months, if released at all. The decade proved a sad one in the hip-hop

community, as the deaths in rapid succession of XXXTentacion, Mac Miller, and

Juice WRLD wiped out a generation of new talent.

The global explosion of

hip-hop and pop, primarily from people of color, reflected two important trends

as the decade was ending. Corporations had a desire to prove they were “woke”

by pushing heavily on DEI aspects of their business model, and this led to more

POC representation everywhere. But this also was an accurate reflection of

where much of the new music was being made. Traditional white-rocker music was

in a definite slump, and even the best music coming out of the indie charts

tended to be dominated by very experimental women (Julia Holter, Circuit des

Yeux, Holly Herndon, Mary Halvorsen), or Black jazz artists like Kamasi

Washington. The latter musicians dwelled completely under mass-market radar, to

be sure, but gave an indication of how even the pop underground was changing.

And when a pop talent with an experimental edge could break the mass-market

charts, as Billie Eilish did in 2019, it only reinforced the point that there

was a place for experimentalism. Lil Nas X and Billy Ray Cyrus also introduced

the world to the first mash-ups of hip-hop and country during 2019.

There were also strange anomalies in the Top 10. Because the charts were now based on what people chose to stream, the Christmas charts might be filled with the likes of Gene Autry, Perry Como, and Nat King Cole, as well as holiday music of more recent vintage, such as Mariah Carey, Wham!, and Whitney Houston. A 70-year-old version of “Rudolph” breaking the Top 40 obviously made it difficult to assess how modern pop was being received.

Bands reuniting in the latter

part of the decade ran the gamut from 1980s favorites like Depeche Mode, to

bands that only recently called it quits, including Panic! at the Disco and

Fall-Out Boy. As all of them went on tour, the concert scene grew more

inflationary and crowded by the year. Long before the post-Covid ticket

scandals involving Taylor Swift and Bruce Springsteen, concert consumers had to

worry about more than the ticket resellers by 2018-19. AXS and other sellers

were playing their first games with “dynamic ticket pricing” for popular artists,

and the price of concert tickets began to regularly reach into three figures –

in fact, sub-$200 prices were considered a bargain for some artists.

Inflation also hit the LP

market in the late 2010s, long before the fire at Apollo Masters days before

the Covid lockdown created a significant lacquer shortage affecting LP prices

globally. If there was a bright spot, the mini-inflationary trends in the music

industry prior to 2020 helped prepare consumers for the supply-chain breakdowns

and concert-less months of the pandemic.

When a global shock of any

type takes place, there is a natural tendency to assume one felt precursors, but

in the case of Covid, the rumblings seemed real. My wife and I visited Los

Angeles to see our daughter at the end of the 2019 calendar year, and snagged

tickets to a New Years’ Eve Guided by Voices show at the Terragram Ballroom

promising “100 songs for 100 bucks.” The show fully lived up to its billing,

and I remember telling my wife at the conclusion that “This was the most fun

I’ll have in quite a while, since the 2020s are bound to bring us multiple

shits hitting multiple fans at once.” If only I knew.