Were the 45 rpm records and spoken-word diatribes of mid-decade 1970s a harbinger of punk or privilege? - 1975-77

Long before Patti Smith’s introduction to

the world at the end of 1975, the paramour of Robert Mapplethorpe had

fascinated me with her New York adventures, chronicled in Creem magazine and elsewhere. I picked up Smith’s poetry

chapbooks Seventh Heaven and WITT before

graduating high school, and was astonished to find she had released an

underground 45 rpm record, “Hey Joe”/”Piss Factory.” I had gotten so used to

associating an LP with innovation and the 7-inch record with mainstream

culture, the prospect of flipping the media expectations jolted my world – and

it wasn’t long before Pere Ubu and DEVO released underground singles, long

before the primary wave of punk hit US or U.K. shores. The arrival of re-imagined

music led to a revival of 45-rpm singles in at least two instances – punk’s

early days in 1976-78, and the grunge-indie launch of the 1990s. In both cases,

the dormant market for 7-inch singles exploded anew.

My last months in high school

were strange times, with the first resignation of a U.S. president in history,

making way for a Michigan native, Gerald Ford, as a temporary stand-in. The

mythical nation of South Vietnam fell in the spring of 1975, youth culture

seemed all but dead, and I put out a couple issues of another underground

broadsheet, Tiger Mountain, in an

attempt to explain it all. I followed the adventures of music writers like

Lester Bangs in hopes of catching new elements of club culture, but except for

hints of new acts being booked by CBGB in New York, I seemed cursed to graduate

under the slogan “May you live in uninteresting times.”

There was certainly a host of

intelligent singers breaking the charts – Phoebe Snow, Harry Chapin, Roberta

Flack. The problem was that they all felt so “grown up.” Top 40 culture had

lost its sense of careless youth, even more so than FM AOR – even though

album-oriented rock had been launched with the intent of being more serious and

grown up than the Top 40. Odd, then, that KISS and similar arena-rock bands

dominated the FM charts. The true start of the disco era was in the spring of

1975, long before The Bee Gees or John Travolta got involved. One band cracking

the Top 40 in that spring was called Disco Tex & The Sex-O-Lettes, and Van

McCoy released his seminal “The Hustle” at the same time.

A big change in electronic

music took place in mid-decade, though its implications did not become clear

until the mid-1980s. Pioneers of both the analog synthesizer and modular synthesizer

made the banks of electronics a visual centerpiece in their own right. Such maestros

included Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson in prog-rock, and Allen Ravenstine in

proto-punk. Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream led a krautrock invasion in

mid-decade that awakened listeners to synthesizers’ possibilities. In 1970,

Moog Music introduced the Minimoog to bring portability to the analog synthesis

world (and Yamaha followed with the portable digital DX7 in the early 1980s).

As krautrock grew in popularity even as the Minimoog dropped in price, bands

that once considered only standard electronic keyboards could move to portable

synthesizers. Many artists from Eno to Pink Floyd to Jean-Michael Jarre

considered the VCS-3, manufactured by London’s EMS, to be the definitive mix of

functionality and portability, and the VCS-3 rapidly became the primary choice

for the touring progressive band. This was a positive trend until 1980s producers

began to over-use the musical style, giving rise to the dreaded “1980s

production wasteland”. In Chapter 9, we will look at how the supposed sins of

the compact disc really reflected poor engineering and production choices made

in pop music during the decade. For now, suffice it to say that decisions made

by bands and individual musicians to add portable synthesizers in the mid-1970s

eventually led to a poorer pop music production environment in the decade to

come.

It took a few months to

appreciate the rich music environment I stumbled into at Michigan State

University in the fall of 1975. Roscoe Mitchell of Art Ensemble of Chicago had begun

a residency there at the start of my freshman year. Two campus organizations, ASMSU

Pop and Showcase Jazz, regularly brought people like Keith Jarrett, Pat

Metheny, Sonny Rollins, Steve Goodman, Bruce Springsteen, and Tom Waits to

campus, while a local bar showcased Captain Beefheart and Patti Smith within my

first year. Even when appealing to a wider student body with a free outdoor

festival, ASMSU chose Bonnie Raitt, Little Feat, and NRBQ for its spring 1976

lawn fest. I had little to complain about.

My father and I shared a few

moments of common musical love by seeing Tom Waits live a couple times in the

1975-76 period, once on the MSU campus. Dad had always had a soft spot for scat

jazz, be bop, and Dixieland jazz (and had his own retro jazz band), while I was

a fiend for Waits’ drunken spoken-word albums from that late 1970s period. Dad

wasn’t always able to follow Waits into the Swordfishtrombone years, but

I gave him good marks for trying (as I would for his efforts with everything

from Zappa to Incredible String Band).

I was also lucky to move into

the Case Hall dormitory with an overabundance of progressive-rock and jazz

nerds. While I knew most of the favorites of my new companions, I grew to

appreciate Genesis, King Crimson, and the jazz artists of the ECM label more

profoundly, due to being fed a constant diet during stoner sessions and keg

parties. Nevertheless, despite the abundance of campus riches, I still felt

overwhelmed with ennui at times. The pop music controversy of the fall semester

centered on Bruce Springsteen appearing simultaneously on the cover of Time and Newsweek.

Those of us who had been with

the Boss for the first two Columbia albums knew that the hype for Born to Run was not unwarranted, yet it seemed producer Jon

Landau was unleashing such Svengali-like powers, he became the epitome of the professional

in Joni Mitchell’s “Free Man in Paris” song, “stoking the star-maker machinery

behind the popular song.” The move augured the rise of the major-label ultra-event,

one factor that drove the reaction of DIY punk in the late 1970s, and later drove

the arrival of 1990s indie rock after a decade of the 1980s where the big

corporations ruled the entire supply chain of popular music. The larger than

life appearance of the first two Fleetwood Mac albums to feature Buckingham and

Nicks, the eponymous 1975 release and

its 1977 Rumours follow-on, set the tone in the

mid-1970s for the type of ultra-event characterized by Michael Jackson’s Thriller! in the 1980s (not to mention Springsteen’s own Born in the USA, which brings us full circle back to the Boss).

Patti Smith’s debut album Horses occupied a unique corner at the end of 1975 with

her spoken-word poetry layered on Lenny Kaye’s minimalist riffs. Outside

Patti’s universe, the initial punks to hit the scene were not enraged barons of

accelerated 4/4 anger, like The Damned or The Dead Boys, but the acts

associated with minimal chord changes and a sardonic dumbing down, exemplified

by The Dictators in 1975 and the debut Ramones album in 1976. Playboy Records

made a very belated release of The Modern Lovers’ 1972 black heart sessions in

1976, which prepared the world for both Jonathan Richman’s childhood regression

in a reformulated Modern Lovers, and Jerry Harrison’s later role in Talking

Heads, which was making some of its first CBGB appearances in 1975. The middle

of my freshman year was when the first zines like Punk arrived,

giving me ideas for later forays into indie publishing in 1977.

There seemed to be fewer

excuses all the time to check out the Top 40 singles of the week. Vapidity was

a description that not only applied to the Barry Manilow breed of songwriters

filling the charts, but also to the tactic of recycling favorite tunes of AOR

FM-radio bands. Both Aerosmith and KISS had re-engineered versions of previous

hits enter the charts in early 1976 – like a summer rerun, and just as

pointless. There also were only a handful of bands, exemplified by The Sweet,

Thin Lizzy, or Bay City Rollers, keeping alive the mid-1960s explosive poppy

hooks. Even bands at the heart of AOR cred could use repetitive lyrics going

nowhere, like Free or Foghat, as well as slow and largely uninteresting

arrangements, like Elvin Bishop’s “Fooled Around and Fell In Love.” This made

the mid-year arrival of The Ramones’ debut album all the more comical and

critical. The four New York revivalists were deliberately repetitive, dumb, and

loud, while waxing on adolescent silly themes. Many found irony in the fact that

Paul McCartney & Wings’ “Silly Love Songs” was at the top of the charts

just after The Ramones’ debut.

Meanwhile, by attending

parties of the MSU cognoscenti, I was learning of releases that qualified as a

true pre-punk underground. They ranged from free jazz and improv, to a

reimagining of issue-oriented folk. Judy Collins’ 1976 release of Bread and Roses sparked a bottom-up folk revival movement that was

leveraged by women and gay groups as well as the nascent anti-nuclear movement,

though because the Bread and Roses movement was decentralized and region-based,

it was invisible to all but a few. Meanwhile, the heady improvisational world,

led by pioneers like Carla Bley, Miles Davis, and Art Ensemble of Chicago, set

a high bar for creativity that few in the rock world could ever hope to meet. This

led me to conclude that if the first two Residents albums, and Bley’s Escalator Over the Hill, counted as a new underground,

that must mean the album-oriented rock that defined my high school years was

middle of the road music. AOR was now MOR, what a decline.

What was true culturally was

true politically and socially, with mid-decade winning the moniker of “Me

Decade” from a media anxious to categorize and declare. Granted, there were

fringe benefits to gazing at one’s own navel, such as the new-found obsession

with gymnasium workouts, never a favorite in hippie years. The years between

Nixon’s resignation and the fall of Saigon on the one hand, and Seabrook and

anti-nuclear environmental concerns on the other, were never more than a brief

hiatus, but the bicentennial represented the trough for political awareness in

the country. True, a few brave anti-nuclear souls initiated the bicentennial

Continental Walk for Disarmament, but except for the event introducing the

world to folk singer Charlie King, there was little traction with youth in the

nation. Gil Scott-Heron managed to turn ennui to the advantage of activists,

releasing spoken-word tracks like “Bicentennial Blues” that bemoaned the empty

state of the decade at midpoint.

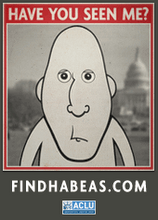

The one moment of furor at

MSU centered on The Iran Film Project, a documentary effort sponsored by the

shah of Iran and the CIA. Because the film was shaping up as a hagiography of

the Reza Pahlavi family, Iranian students were incensed, but dared not come out

in public. The protests of hundreds of students wearing blank square white

cardboard around their faces set the tone for 1975-76 on campus, as did chants

of “The shah is a U.S. puppet! Down with the shah!” (I was overjoyed to see

Patti Smith later post a picture of herself surrounded by Iranian students with

their paper masks.)

It’s funny how both the

arena-rock AOR traditionalists, and the protopunk malcontents, focused with

equal fervor on disco as a symbol of all that was wrong in the world. Granted, disco’s

exaggerated class distinctions and dress-up fake aristocracy seemed tailor-made

for parody, so it would be difficult for many outside the mirror ball world to

hold their tongues. But amidst all the Bee Gees and Average White Band

soundalike hits, there were moments of pure enjoyment, characterized as guilty

pleasure for the disco haters. Donna Summers’ “I Feel Love” (the first hit with

a completely synthesized beat) stood out, as did Earth Wind & Fire’s

“September,” KC & The Sunshine Band’s “Keep It Comin’, Love,” The Brothers

Johnson’s “Strawberry Letter 23,” and so many others. A girlfriend dragged me

to my first gay bar, Trammpps, during those years, where I got to witness a

Cockettes chorus line dance to an augmented version of Polly Browne’s “Up Up Up

in a Puff of Smoke.” Those kind of memories have as much staying power as one’s

first Talking Heads or DEVO concert.

My own deepest plunge into

mediocrity during those months happened not with disco, but in a spontaneous car

trip to Newport News, Virginia on the bicentennial weekend to drop off a

friend. On the return trip, we stopped in Nashville for an outdoor Peter

Frampton and Gary Wright festival that might have had some debauched moments,

but seemed at the time to be the height of empty arena rock. During the late

summer of 1976 I made a point of listening to more Ramones and following early

press coverage of the Sex Pistols in London, just so I could feel a middle

finger could be appropriately delivered to some corner of mainstream culture.

It wasn’t until the punk wave crested in 1977-79 that I started asking if there

was a method behind that particular madness.