The rise of Discus Obsessivarus, or "Collector Scum" - 1970-72

Our tumble-down Victorian house was badly in need of a facelift in the

summer of 1970, and the teenage dynamic duo of Dave and Nate proved up to the

task of hanging off eaves and leaning backward off balconies. They were

surprised that a precocious and annoying 13-year-old was well-versed in bands

that mattered, but they expressed shock that I hadn’t already joined a record

club to maximize my listening options. They helped me scan the Columbia House

12-for-a-penny list, and my introductory package of LPs included the debut

eponymous albums of Johnny Winter and Eric Clapton, Janis Joplin’s Kozmic Blues, Traffic’s John Barleycorn Must Die, Joan Baez’s One Day at a Time, and

other titles lost in the haze of a half-century. Not only was this a rich

initial feast to be augmented every few weeks by supermarket purchases, but

albums made an ideal present to beg from relatives – Crosby, Stills, Nash &

Young’s Déjà vu and Led Zeppelin’s III were Christmas presents for the new era. I quickly got my first exposure

to releases outside the Columbia House mainstream. My introduction to glam, for

example, was Alice Cooper’s Love It to Death. It’s

fair to say that many youth not yet in high school became album-heads in late

1970, in part because of the media hype surrounding the back-to-back deaths of

Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix.

Somewhere in the early 1970s,

I joined with millions of other “serious” music fans in losing interest in the

Top 40 and pop-music radio in general. Sure, I’d consult the lists in the late

1970s to see how punk was faring, against both disco and teen heartthrobs like

Andy Gibb. Even in the 1980s and 1990s, I was dimly aware that a Top 40

existed, but radio (at least the continuous-hit variety) seemed like an

irrelevant environment by that time. In the 21st century, songs were

introduced primarily through playlists, or as soundtracks to popular shows, but

still the Top 40 survived in odd little I Heart Radio niches. But the mere fact

that I could zone out one music media venue so quickly in 1970 gave me an

object lesson of how young adults leaving their high school or college years

could suddenly zone out on musical interests in general. The fleeting nature of

consciousness makes it all too easy to practice tunnel vision.

I juggled multiple budgets in

order to stay current with new LPs, while trying to fill back catalogs of the

weirder artists that really appealed to me, like Frank Zappa and Captain

Beefheart. The Ann Arbor/Detroit collective of musicians loosely associated

with John Sinclair – including the MC5 and Iggy and the Stooges – made me feel

as though Michigan was an important defining base for radical culture. So what

if Sinclair and his White Panthers were slightly behind the West Coast? John

Lennon, at the peak of his radicalism with Yoko, always seemed a year or two

behind the times, but that did not cut into his effectiveness. Wayne Kramer and

Rob Tyner from the MC5 taught me what “rhetoric” meant, while Iggy, already a

terror to middle-class parents in 1970, prepped me for the glam-rock era when

his re-formation of The Stooges put the band in the center of the Bowie-Reed

crowd. I remember my parents telling me in 1970 that they didn’t mind most of

the bands scheduled to play at the Goose Lake festival, but “that Iggy, he’s

just a threat to society!” Yep.

The deaths in rapid

succession of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison predated a distinct

fragmentation among not-so-underground AOR artists. Joni Mitchell and Neil

Young were among songwriters opting for heady introspection, and savvier

listeners were turning to borderline introverts like Nick Drake as well. British

hard rockers like Led Zeppelin were setting the stage for a brasher (and more

predictable) class of rockers ranging from Humble Pie in early days to AC/DC

later in the decade. In fact, Led Zepplin’s diverse and superb III album did not get the audience it deserved because O.G. fans insisted

it didn’t “rock out” enough. In the latter years of driving to cassette and

8-track tapes, this particular listener of “heavy music only, please” became

increasingly annoying (see Chapter 5). This put innovative songwriters like

Pete Townshend in something of a quandary – how would one strive for something

akin to a concept album while rocking hard enough to please the masses? (In the

case of The Who, percussionist Keith Moon solved the problem by treating any

composition with a bit of manic intent.)

Because 1970-71 represented

the precipice before the arrival of Ziggy-era Bowie, Blue Oyster Cult, and many

other larger-than-life acts, it’s easy to forget how conservative AM pop radio

became by late 1971, as though everyone needed a rest. There was more

Carpenters, Bread, Cat Stevens, Cher, and Carole King than ever before. John

and Yoko, after a string of provocative singles, released the era-defining Imagine in 1971. It felt as though the world needed a

break after living through 1960s chaos. Entering high school in 1971 might have

meant frosh dances in previous decades, but I was head-down obsessed in album

rock. Getting stoned was still a couple years away, but there already existed

an attitude of taking music too seriously that interfered with the physical joy

of an upbeat pop song.

As late 1970 waded through

1971 and into 1972, singles experienced more longevity on the charts – both for

decent songs like Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition,” Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me

Softly,” or Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain,” but also for the dreck that made up

most of the Top 10. Some chart analysts say it was the vacuity of the charts in

the latter half of the 1970s that pulled people to either punk or disco (with a

smattering of true rap options just beginning in that era), but a more careful

examination would prove that the singles charts had lost most of their sparkle

even as the 1970s began. Hence the domination of the 40-minute long-playing

album in that decade.

Just as some entering high school became obsessive statistics gatherers of a favorite outdoor sport, or detailed monitors of TV shows and movies, I was one of the music nerds who ordered Schwann LP catalogs so I could develop a full picture of musicians in the pop and jazz fields. It was Schwann that introduced me to several fringe artists of the underground-beyond-underground, from Patrick Sky to Pearls Before Swine.

My

pledge to follow liner notes as closely as some follow score cards only lasted

a decade or two, as I learned much later in life of all the details I failed to

pick up by neglecting the smaller-print liner notes for CDs. It wasn’t long

before I learned about music fidelity, though I lived with crap turntables and

preamps for years. It was only through the college-age older siblings of

friends that I learned names like Technics and Sony. Given the 21st-century

vinyl revival based on the supposed better fidelity of an analog source in

reproducing sounds, it seemed ironic that the two formats to challenge LPs in

the 1970s, 8-track tapes and audio cassettes, took market share from LPs based

on their portability and ease of use, since their fidelity was hardly

comparable to vinyl.

It’s easy in retrospect to

forget how significant the growth of LP sales was in the first half of the

1970s. In the watershed year of 1970, more than 500 million units were sold

worldwide, amounting to 40% of all physical media. The numbers sold per year

remained above 300 million well into the 1970s, when cassettes in particular

began edging out vinyl sales. While much ink has been spilled over the 21st-century

vinyl resurgence, particularly after prices surged in the wake of pandemic

shortages, the number of LPs sold in 2022, for example, registered only 41.3 million

physical albums (8.2% of 1970 totals), accounting for 43 percent of physical albums sold in that

year. Statista Inc, is quick to point out, however, that if streaming and

downloading is factored in, LPs accounted for only 5 percent of equivalent

album listening in 2022. Thus, 1970 represented the top of the curve in several

senses.

The early 1970s also

represented a big change in how recorded music was marketed, changes that

carried through the CD-replacement era and even into the streaming 21st

century. Prior to the LP boom of the 1960s, most people bought LPs, 45 rpm

singles, and even the 78s that preceded them, in supermarkets, variety stores,

department stores, and, within the Black community, barber shops and beauty

shops. The true record store was limited to large urban markets, and often

specialized in old collector 78s (in the recent film A Complete Unknown and the TV series The Marvelous Mrs.

Maisel, one can get a sense of what the record store of the 1950s and early

1960s was like). The dedicated independent record store arose in concert with hard-rock

and stoner cultures, and often co-existed with head shops in many cities. Large

chains like Sam Goody and WhereHouse expanded as suburban shopping malls opened

in the early 1970s. Initially, the chains were best positioned to take advantage

of the shift from LPs to CDs, but by the new millenium, most chains had been

driven out of business by the shift to streaming. We’ll discuss the special

case of Tower Records later. (It’s interesting to note that the same thing happened

in books – first, big chains like Borders swallowed independent bookstores, but

Borders itself went out of business by 2015, leaving only Barnes & Noble as

a survivor that was able to sell both books and CDs/LPs in brick-and-mortar

stores in a 2020s economy.)

Many independent record dealers

shifted in the course of the 1970s to a mix of new and used products, becoming the

buy-and-sell equivalent of vintage stores. This allowed many independent

dealers to survive the shift in the 1980s to CDs, and the later sparse years as

downloads and streaming took over. The best independent dealers had to be

flexible – they had to clear space for 7” 45 rpm records during the revivals of

that format in the late 1970s and early 1990s, and they had to be ready to

accommodate different format spaces for CDs. It didn’t take long for customers

to move to regular lamentations when an independent store went under, but over

the course of the next 50 years, there was no great lesson to learn about an

industry that some thought was on the verge of extinction. Somehow, the

independent music dealers hung on, and still do today.

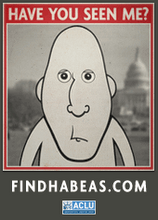

The evolutionary rise of the

creature known as “Collector Scum” happened slowly and subtly. Before the

advent of tapes or CDs, corporate labels released only mono and stereo versions

of an album (and mono ended up being the one with more collector value over a

50-year period). Occasionally, you might get production mistakes that would

result in higher prices for a supposedly flawed product – The Beatles’ banned

“butcher-block” cover for Yesterday and Today was a

perfect example. But the more collectible LPs arrived courtesy of the plausibly-deniable

pirates who released bootleg LPs, specializing in live performances or

unreleased demos from top-selling artists. One of the finest legacies of the

1970s bootlegs came in the experimentation with different colors of vinyl for

the LP, not just a yellow or a transparent red, but even splatter-rainbow

colors for some choice bootlegs. The vinyl revival of the 21st

century brought with it the return of special colors of vinyl for

limited-edition LPs, but few remembered that the pirate manufacturers of the

1970s are the ones who really brought colored vinyl out of the preschool

children’s-specialty market, and into the rock mainstream.

In the final months of junior

high and the summer prior to entering high school, I experimented with

producing a mimeographed equivalent of an underground newspaper, though the

cultural issues to get excited about were only a whisper of the 1965-70 period.

City-specific tabloid alternative newspapers were expanding tremendously in the

1971-74 era, like the Lansing-area Joint Issue, later to

become Lansing Star. But except for the occasional

large demonstration, these newspapers’ claim to a counterculture centered

primarily on recreational drug use. Even as Richard Nixon’s Vietnamization made

the prospect of a draft slowly wind down, there still were significant protests

against the war, and in favor of nascent women’s rights, gay rights,

recognition of indigenous people. Yet although memoirs from Abbie Hoffman and

Jerry Rubin became best-sellers, there was a definite feel by late 1971 that

youth revolt had entered a waning phase.

If drugs were the only

countercultural option around, then that would be a necessary accompaniment to

music. I tried weed for the first time just shy of my 15th birthday,

in the spring of 1972, and added a few hallucinogens not long after. It

provided an interesting perspective, but I looked on in frustration as a

significant number of teens seemed to prefer the new downer, Quaaludes, which

failed to attract my interest at all. My definition of altered consciousness

centered on artists like Zappa and Beefheart and the related mind expansion,

not in hollering “Yeah!” to down and dirty blues. That cleaving was the first

parting of ways I experienced from mainstream arena hard-rock, as I spent more

time with glam rock, progressive rock, and experimental artists.

In three weeks - Chapter5 - Tapes, Taping, and Subgenres - Struggle for Market Dominance

Copyright 2024 Loring Wirbel